REMEMORY

An installation explored a potential mourning practice in the digital age, offering a possible conclusion to our digital memories.

SUMMARY

Role: UX/Industrial Designer, Developer, Maker

REMEMORY is my thesis project for the Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP) at NYU. Over the span of one semester (4 months), I started researching (although I have been exploring this concept for years) and went through the following phases: User Interview, Industrial Design, Interaction Design, Prototyping, Iteration Design, Circuit Building, and Digital Fabrication. As I executed my project I received help from other ITP students and professors. I really appreciate the help they provided as I brought my idea to life.

PROBLEM

In the 15th century a spiritual leader named William Caxton wrote about ars moriendi, which he described as the beautiful death. For him, there was a correct way to die. I took this idea to heart as I started my research on how to achieve beautiful death for our digital legacies. Drawing on the world's traditional funeral cultures, which have been constructed to take care of everything after we die, mainly focusing on how to deal with our physical possessions. Since the invention of the digital, however, there has been considerable uncertainty about how to give our digital legacy a similarly correct way to end.

I started my project by thinking about the following facts:

Traditional funeral culture does not generally consider digital legacy as mourning object. Why?

What makes the current solution of saving data somewhere after someone's death so people can check it online not ideal?

What are the reactions and feedback from people who have online mourning experiences? This can be helpful to better understand the above.

My next step was to start interviewing people...

PROCESS

INTERVIEW

Prior to starting the interviews and questionnaires, I wrote out three assumptions regarding death, digital memories, and mourning. I had identified a lack of proper forms of digital commemoration. From this realization arose the following assumptions on which my research would be built:

Facebook is not designed for online mourning practice. It is obvious that the ways people mourn on Facebook is not ideal.

Part of the motivation behind digital mourning is the fact that people care about digital memories.

Even if the digital experience is not optimized, people continue to mourn on Facebook, highlighting how powerful digital memories are.

With these assumptions in mind, I started the User Interview phase of my research by conducting both face-to-face interviews and anonymous online questionnaires.

Three of my primary interview questions were:

Did you feel strange while checking a deceased person's Facebook page? Why?

If YES, why do you continue to do so?

What did you do when you visited the deceased person's Facebook?

You can find the questionnaire here.

The outcomes from the interviews/questionnaires proved some of my assumptions

Do you feel strange while checking deceased person's Facebook page?

In this question, 8 out of 12

subjects chose YES (2 of them chose A LITTLE BIT).

What did you do when you are visiting deceased person's Facebook?

This question is multi-answer. Only 1 person chose the last option,

2 people chose "Leave your wish and comment".

6 people chose "Checking past interactions with him/her"

If your answer for the question on the left is YES, why you still doing that?

7 out of 8 subjects claimed that

there is no other choice. 1 person chose "other"

Do you think sharing your feelings with others is important in terms of mourning someone?

8 people chose "Yes", 2 for "No". The outcome of this question seems

like against the outcome of the question on the left, however, merging

these two contradictory answers together will give you another fact.

Takeaways from user research:

The current online mourning experience is not ideal and feels strange to many people.

The need to mourn digitally is real, but it is not being sufficiently met. People keep using Facebook for online mourning since they do not have other choices.

People do not generally expose their sorrow easily on Facebook. Instead, they would rather passively check others' reactions rather than actively leave their own comments.

Surprisingly, when I asked "Do you think sharing your feeling with others is important in terms of mourning and remembering someone who passed away?" 8 out of 12 subjects said "Yes." This is contrary to the previous takeaway, which demonstrated that Facebook cannot provide an ideal interface for people to share their feelings.

RESEARCH

In the user research phase, I figured out that users wanted a better and different online mourning experience. However, what experience did they want? I realized that before I get close to the answer, I first needed to know what the mourning experience was. What does mourning feels like and how do people reach their desired experience?

Long research story short, I found most of the answers in this amazing book: Death, Memory and Material Culture by Elizabeth Hallam and Jenny Hockey.

The three key words that best describe the mourning experience are TIME, LINKAGE, and EXTENSION.

TIME

The perceived duration of an object — its capacity to endue time and to operate across time by encoding aspects of the past or future in the present moment — is crucial to its memory function.

Objects constructed of stone, wax, ivory, paper, or flowers have different abilities to endure through time.

What about digital objects?

Conclusion: Digital objects have can endure throughout time longer than material items. However, digital objects may also be the least representative of a person precisely because of their timeless quality.

LINKAGE

When we lose a man, we lose a physical existence (not going to argue about the dualism of body and soul here).

We look for anything and anyone that is linked to this lost man. It is the LINKAGE we are looking for. We try to balance our own emotions by finding these LINKAGES or creating new LINKAGES.

What about digital objects?

Conclusion: Digital objects do have great linkages associated with the person who created them, however, the digital objects' linkages are not material.

EXTENSION

"NEVER FORGET" (9/11). We will eventually forget the hatred we felt, but we will never forget those who died. We keep them "alive" by NEVER FORGETTING any of them. We have become an extension of their lives.

Funeral culture achieves this ultimate goal. The Pyramids, Terra-Cotta Warriors, and 9/11 Memorial all are extensions of people who have died.

What about digital objects?

Conclusion: Theoretically, digital legacies can last forever which makes them the perfect extension of a deceased person's value and social influence.

DESIGN (EXPERIENCE & VALUE)

As a UX designer, I care about user engagement a lot. Saving digital memories on a website provides a solution to the problem of where to keep this data. Without focusing on user engagement, however, it fails to provide an answer to another problem: How to make a legacy meaningful by triggering loved ones to continue visiting and viewing the website? Repeat visits and views is the only way to enhance the potentiality of the object to be a better EXTENSION.

The challenges I faced were the shortcomings I mentioned in the Conclusion sections above:

Give digital memory a sense of time (not just simply showing mm/dd/yy, hh:mm:ss).

Digital memory must be linked to the deceased directly. By this I mean the digital experience should mirror the experience of holding and looking at a photo of his/her loved one. The digital experience needs to be immediate and engaging so the traditional process of "Turn on computer→Open browser→Log in" is not an option.

The biggest challenge is realizing that the essential quality of an extension is to trigger constant visiting by users. The extension absolutely cannot make users feel that it is forcing memories upon them.

Eventually, I decided to build an interactive flipping board installation that connects to the cloud where all the digital memories between the user and the deceased have been saved. REMEMORY works like a regular clock, but it turns into an interactive digital memory flashback device when the user miss the deceased.

Through the daily act of checking the time, I indirectly remind users of the passage of time. Slowly, the user simultaneously experiences mourning and the passage of time, but without overwhelming the user with an onslaught of digital memories. Instead, the process can be as natural as glimpsing a photo of a loved one on the wall.

Illustration:

a. When used as a clock, Arduino Yún connects to the Internet and updates the installation to instantly show the current time.

1. When the installation has been triggered (by putting your cellphone into the slot on the top of the installation), Yún requests a piece of memory (text) from the database. Meanwhile, Yún informs the server that if there is any multi-media content along with this memory, send it to Twillio.

2. The server sends text to Yún and multi-media content to Twillio (if there is any).

3. Twillio sends the content it received to the user's cellphone.

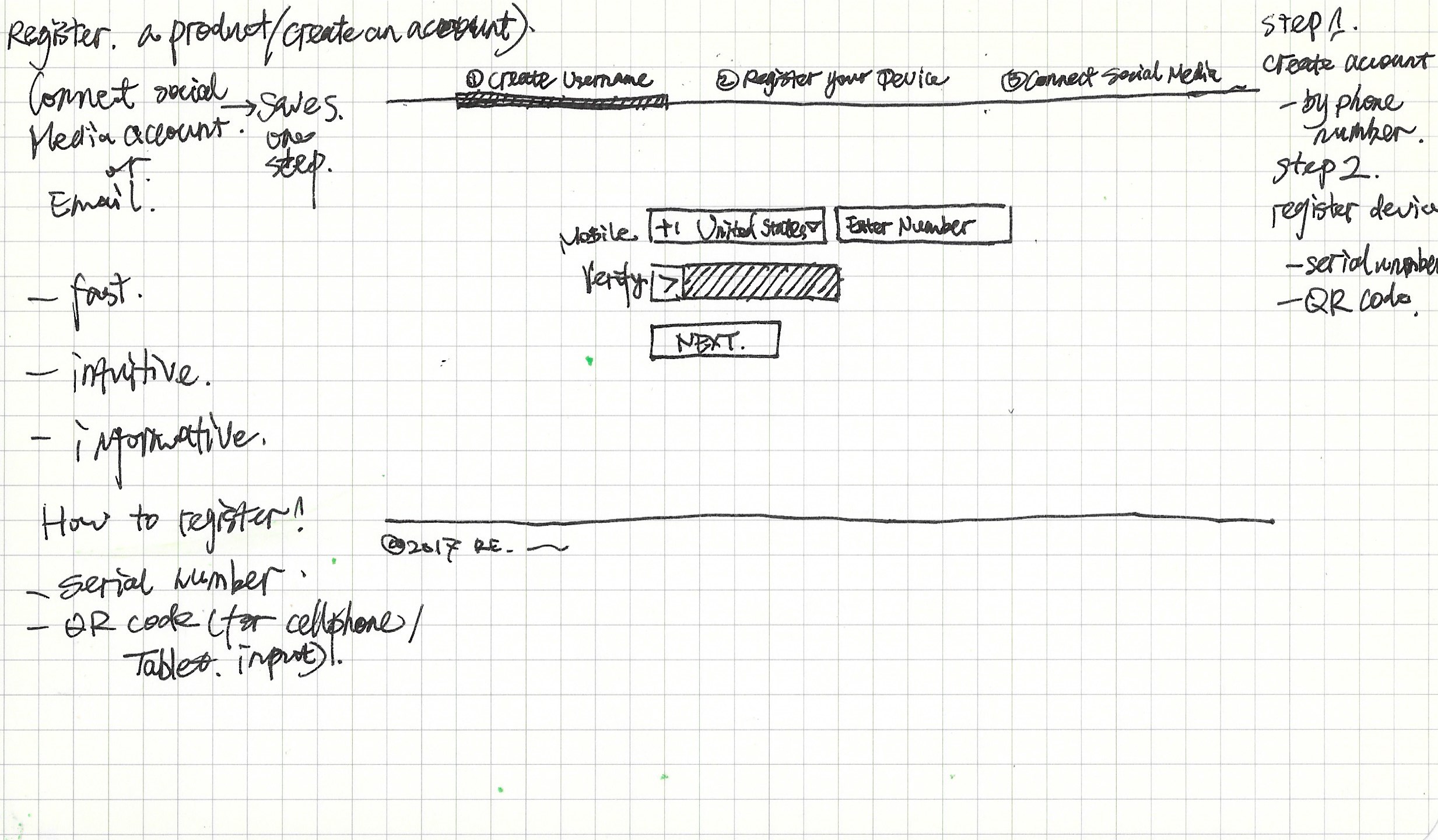

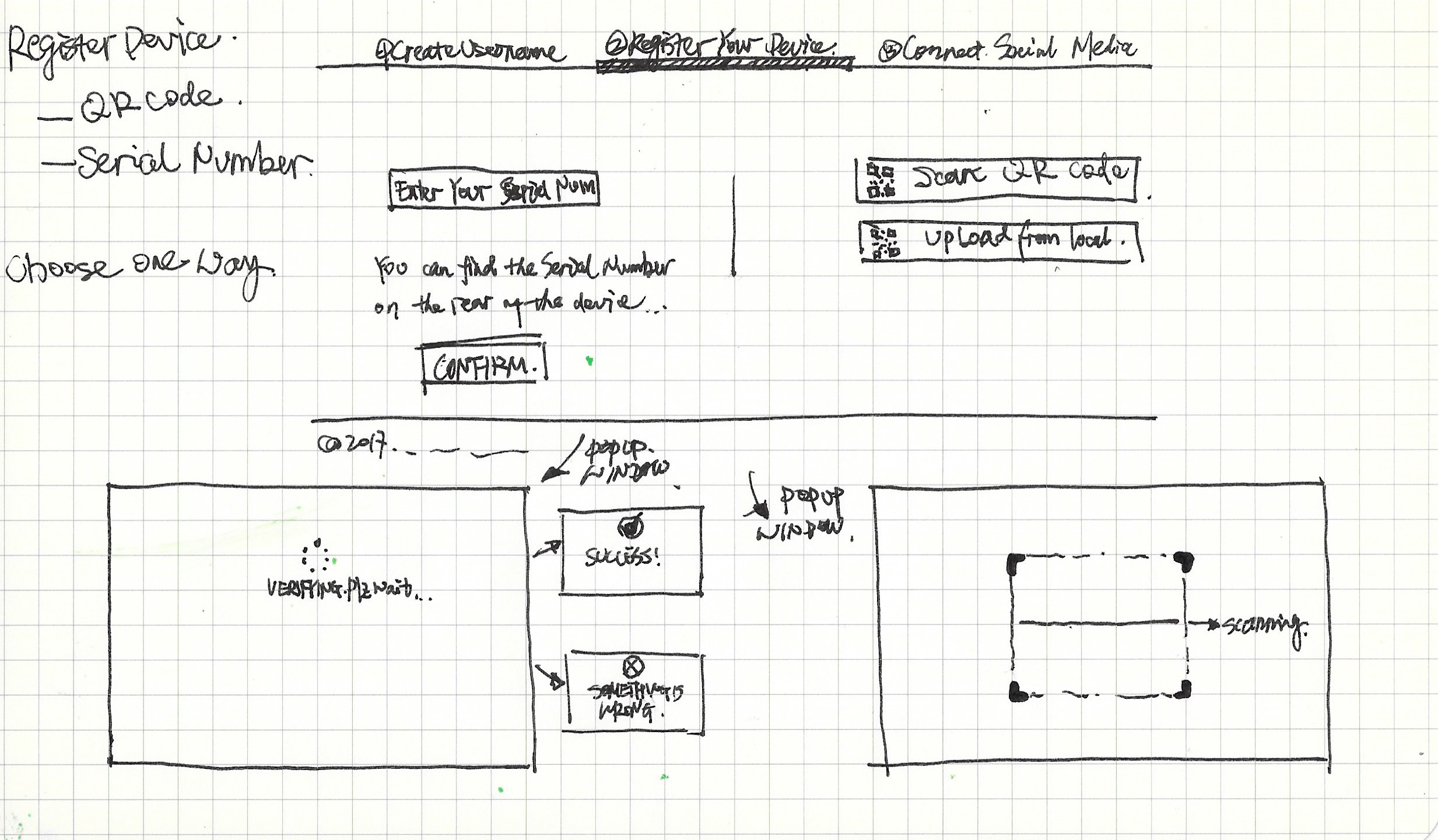

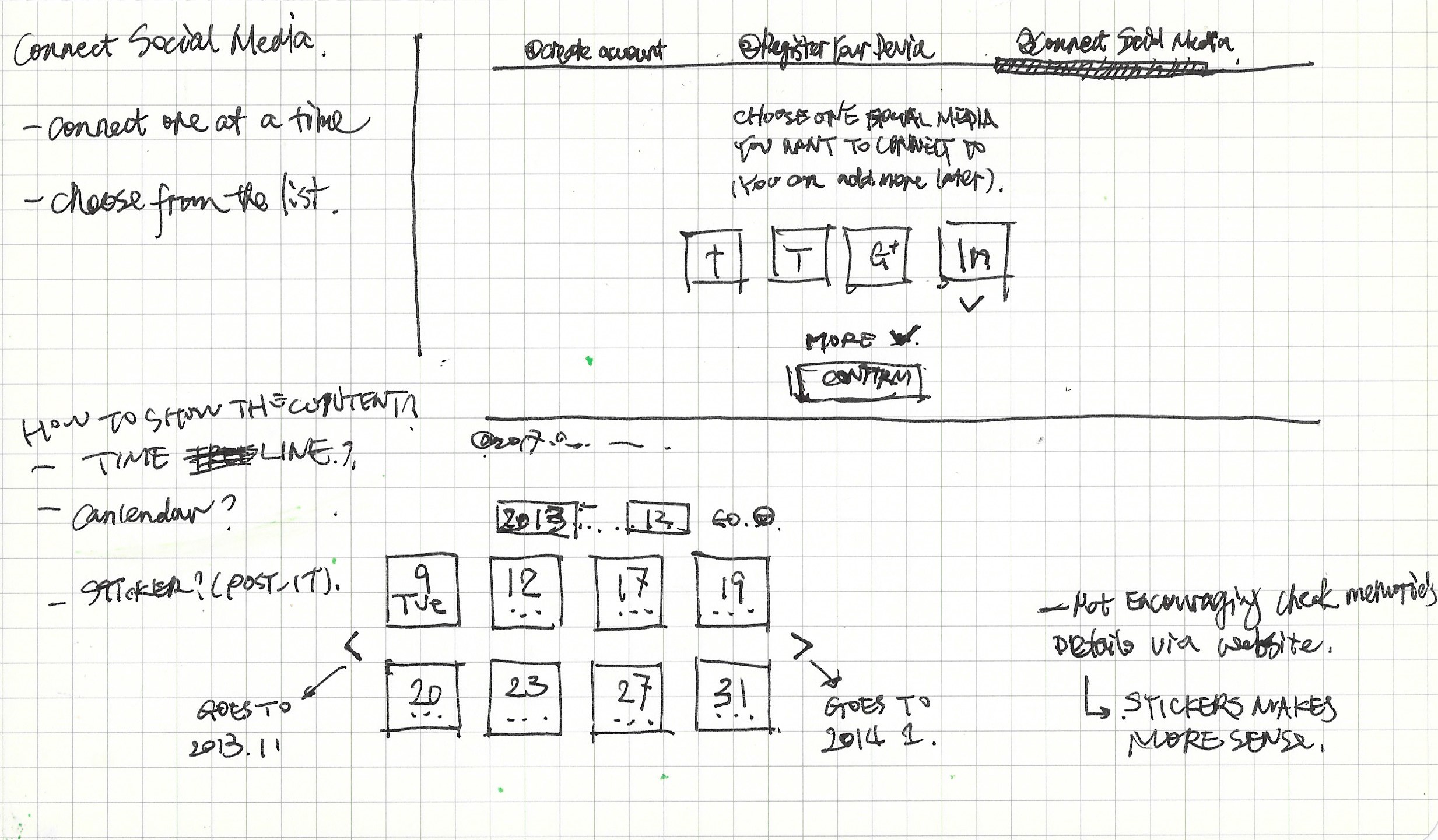

DESIGN (FRONT-END PART)

This prototype is showing how easy it would be for users to sync their social media memories (Facebook in this case) to REMEMORY via a web browser. Ideally, the website itself is just a portal where users register the device online and link their Facebook account with REMEMORY's server, as well as basic checking of the synced memory functionality.

I started this process with sketching (of course). I did not spend too much time on this section since it is not a part of the core experience of this project, as a result, I created an interactive prototype to test it out and see how it works.

DESIGN (PHYSICAL PART)

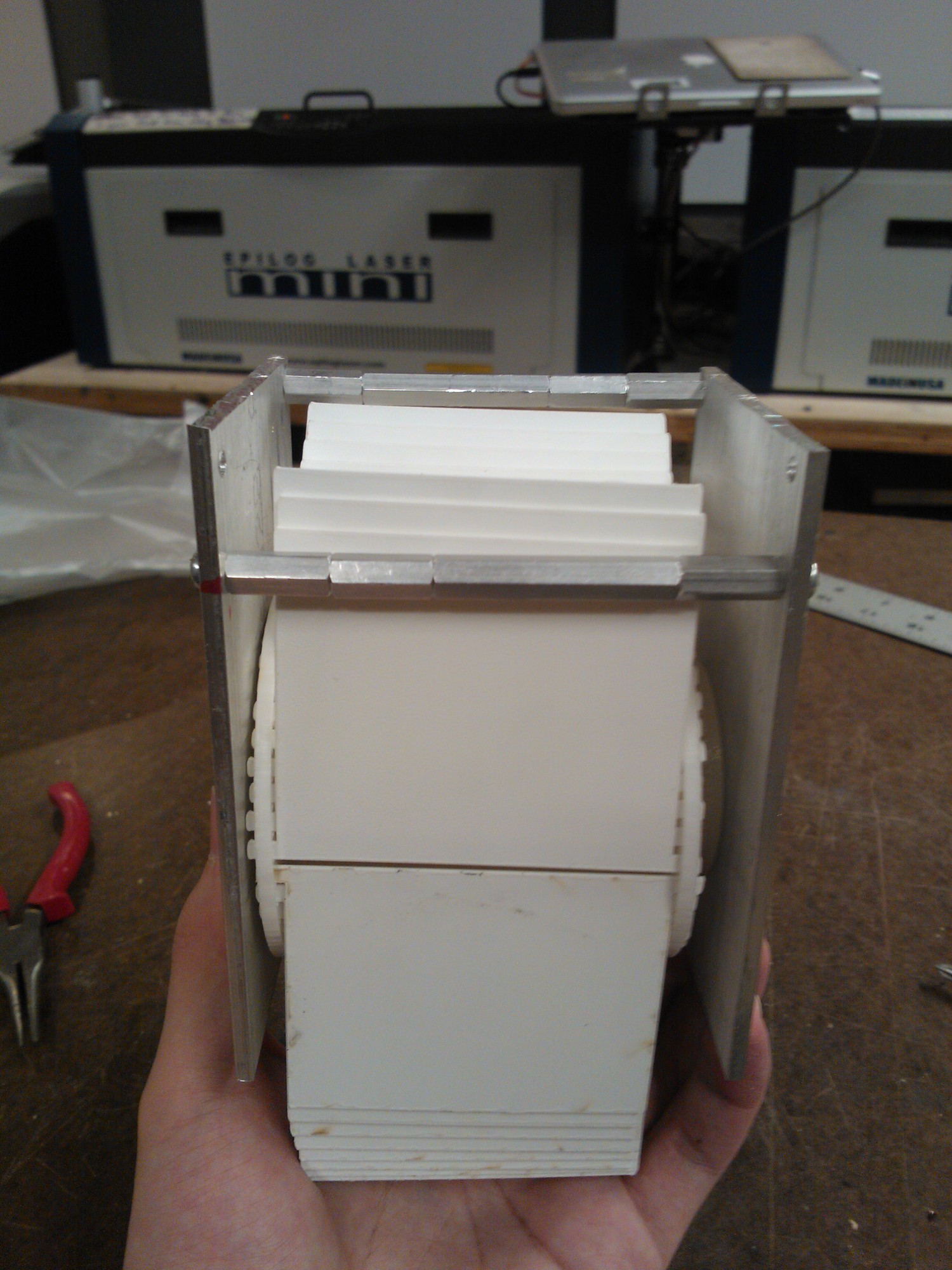

Phase 1:

Here are some of the materials I needed to build the physical device: Stepper Motor, Pulleys, Magnets, Hall Effect Sensors, Stepper Motor Drivers, Gears and Aluminum Board, Wood Board, and Acrylic Board.

The main limitation for this part of design was that I have to figure out how much space the individual digits will take up. By multiplying by 6, I had a rough idea of the size of the whole installation.

For more information about how to make a flip clock, please check out these awesome resources: BeachLab maker space in Europe, and Tom Lynch's work.

On the right side is the final illustrations of the design. I left the bottom part open to highlight the movement of the flipping board. The slot is on top of the installation where user put cellphone in it to trigger REMEMORY to show memories.

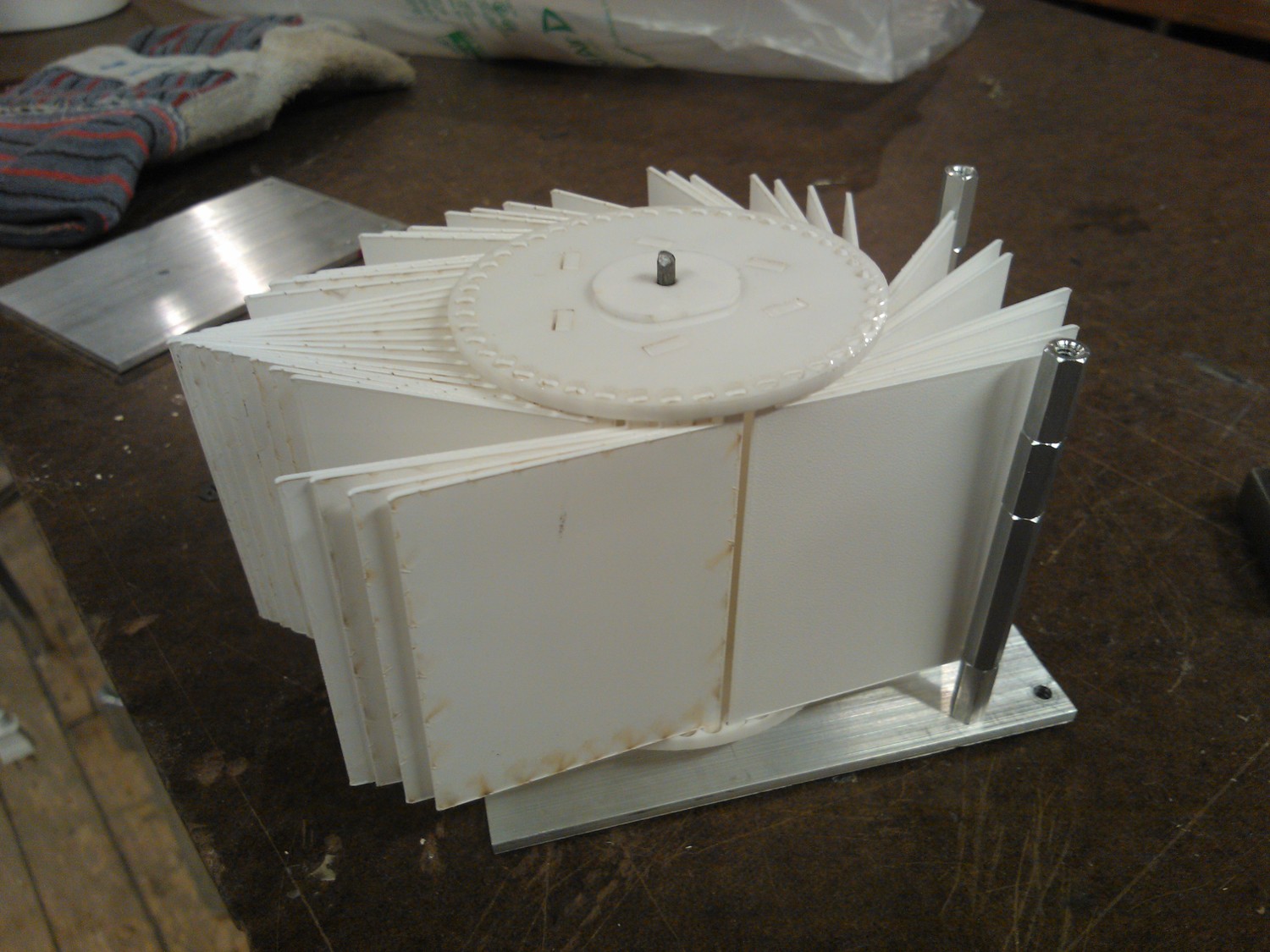

Phase 2:

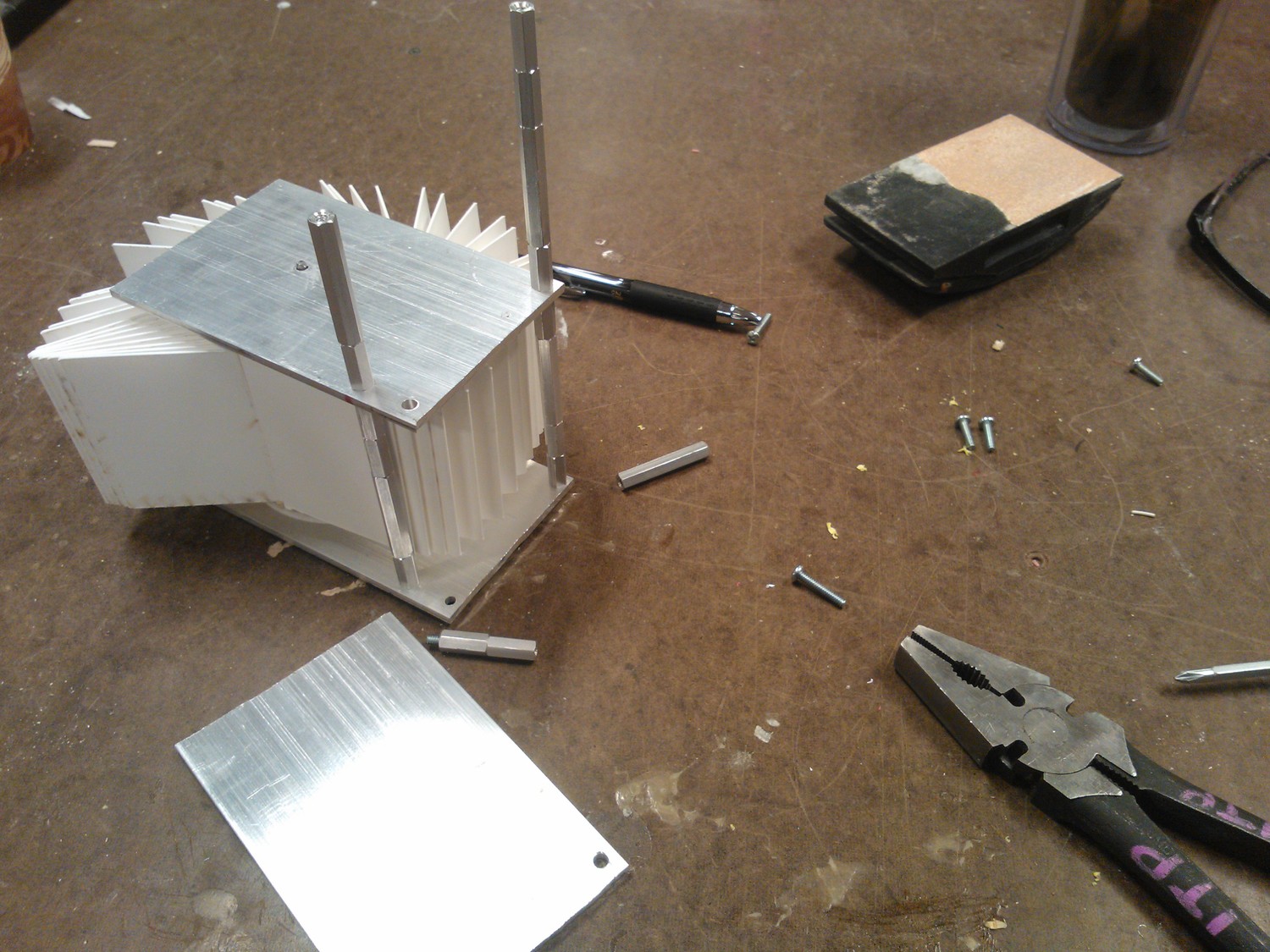

I started the second prototype -- this one made of metal. Using metal to prototype gave me a sense about the reliability and size of all six digits.

Phase 3:

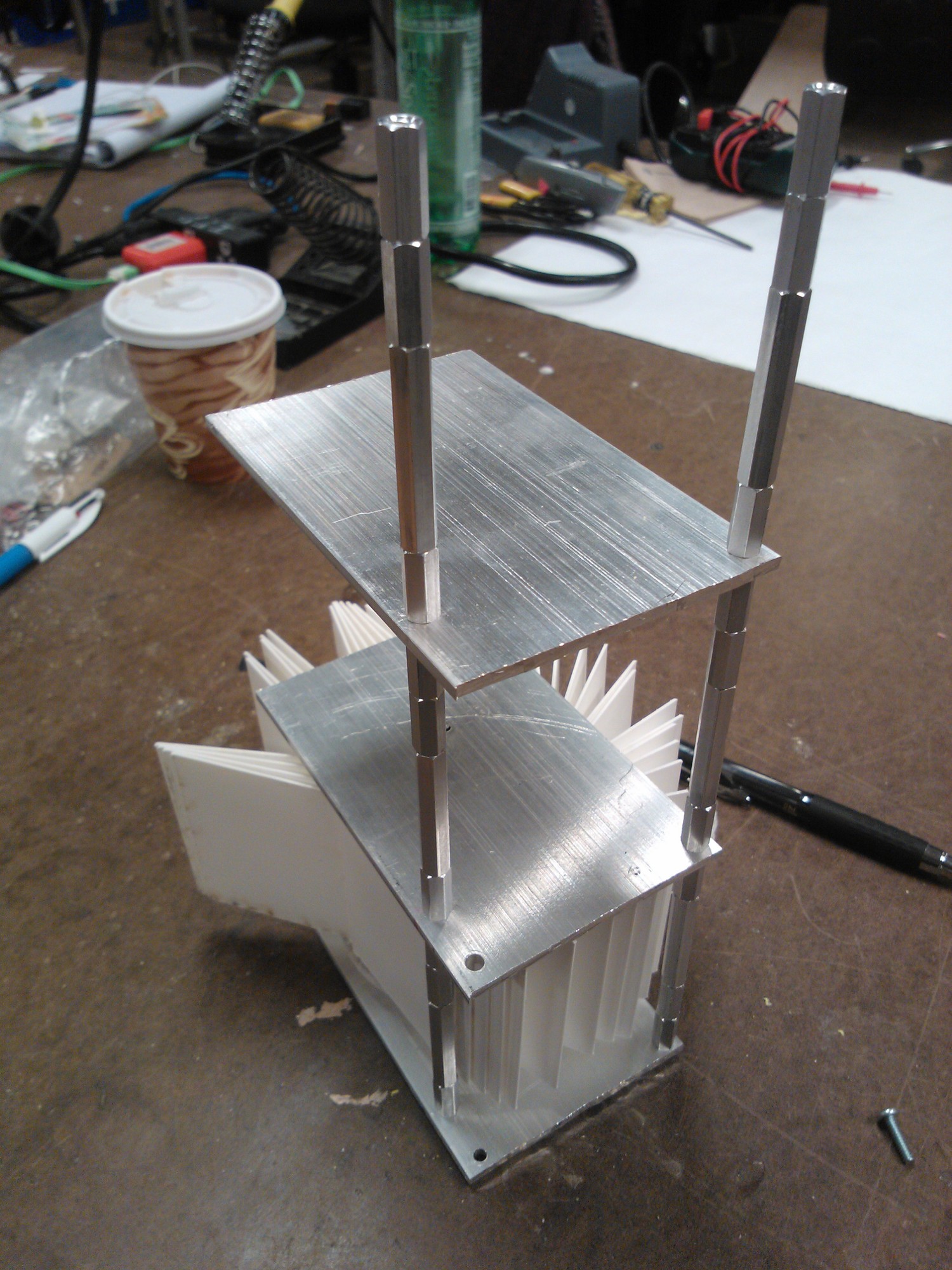

Workable digit. Put everything together. The goal of the third prototype was to have a working digit. The details of the design and building had to be reliable and in working condition.

Each digit has four wires from Stepper, three wires from Hall Effect Sensor, or seven in total. For all six digits there were 7*6 = 42 wires. The large number of wires is ultimately why I used ethernet cable for the final design.

I used Hall Effect Sensor and a tiny Magnet to calibrate the digits so that Arduino would know the start and end point of the wheel.

You can check out the video below to better understand how I calibrated the digits.

3D printed mount, and gears. Putting things together to get a rough sense about the size of one digit.

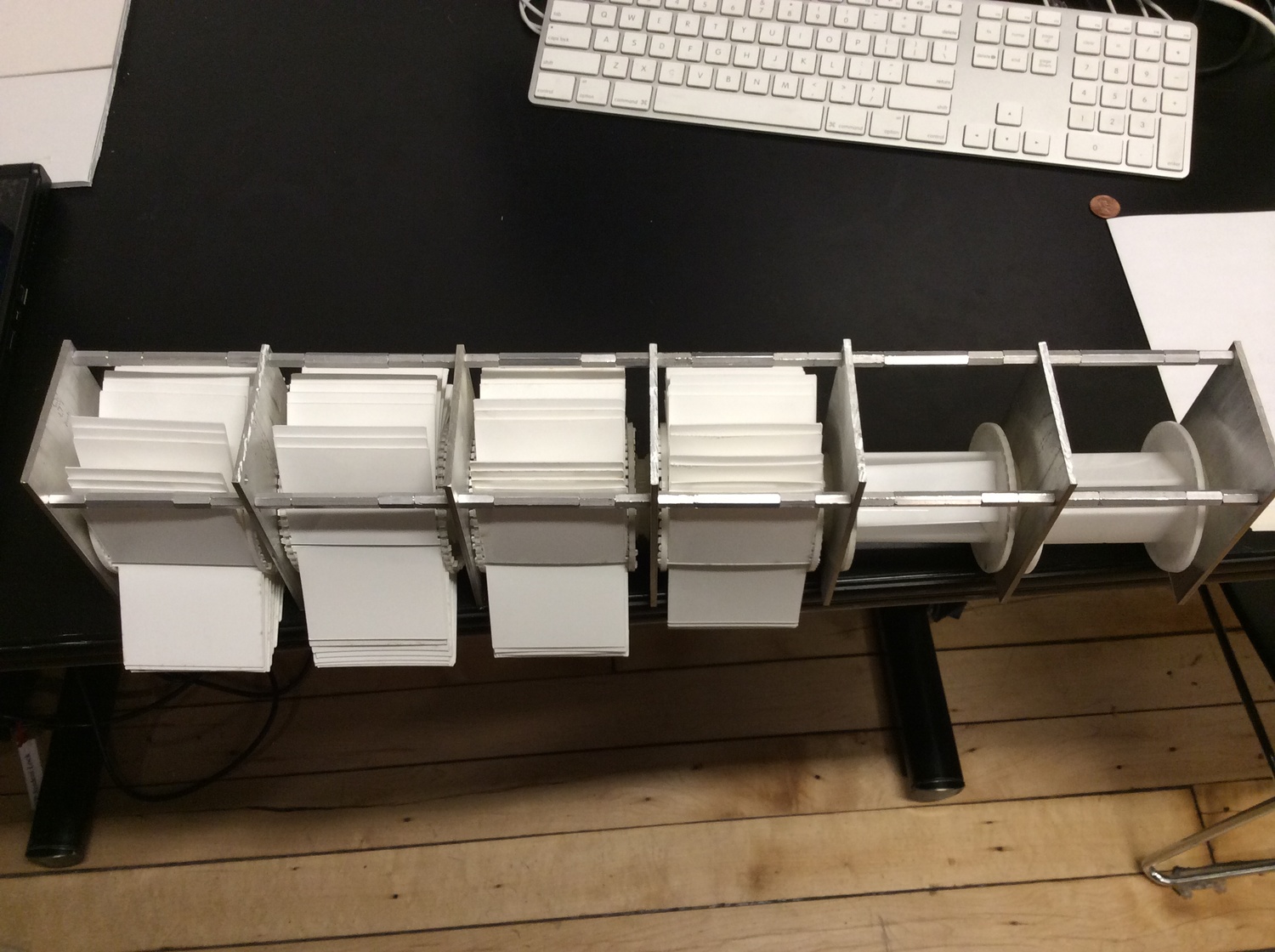

Phase 4:

Expand to a full six digits. It became increasingly challenging as the project scaled up both physically and digitally. I had to adjust the tension between each Stepper and Pulley. The metal frame also started to bend because the digits became really heavy, which meant I had to attach the frame to the wooden top. Finally, there was more code to write for Arduino Yún.

The video below shows how the calibration works. When the installation has been turned on and connects to the Internet, it will automatically calibrate and locate the "0" point on each digit (which is "A"). Following calibration, it will show the current time. In the video, however, you can tell that some digits are several steps off. This situation was improved later.

Phase 5: (Final Stage)

In the final stage of this project, I spent most of the time adjusting the whole physical mechanism, mostly to make sure it was running as accurately as possible.

Here I am going to show you what the user flow looks like in illustrations and video.

P1. REMEMORY usually shows current time as a regular flipping clock.

P2. When it's been triggered, it starts flipping to show a random digital memory from the cloud.

P3. It will show when the memory happened. In this case it is 2014/12/09 which is my birthday.

P4. It starts flipping to show textual content of that memory after showing the time.

P5. Here is an birthday greeting from my dear friend Justin: "HBD Ranimal!" (Ranimal is my nickname.)

P6. Since there are only 6 digits. So it will keep updating the whole memory until it's done.

P7. Once the installation has finished showing the text, the user's phone will receive the multi-media content if that memory has any.

P8. The installation will flip again to show the current time after several seconds.

P9. The whole user flow is done. The only thing the user needs to do re-trigger it is to put his/her cellphone into the slot.

FINAL

I was so grateful to finish this project in such a packed time schedule. It would have been impossible to make it without help from my friends and professors. There were two things, however, that would have benefited the project and the overall process if I had had more time:

Spend two more weeks to conduct user testing and research with a more thorough competitive analysis.

Finish the front end more thoroughly and test it to get greater feedback.

REMEMORY is the first project to come out of my research on digital funeral cultures. I believe there is huge potential and possibility for future projects that tackle digital legacy. At the same time, this is a controversial topic, and one that involves many legal issues. REMEMORY, however, seeks to avoid many of the more sensitive issues.

The user does not have full access to the memorialized account's content. Instead, he/she only gets access to the the content that relates to the user. For example, if the user left a comment under a photo of the deceased, the user can recall that memory, but would not have access to a post from the deceased's mother.

This idea is based on the fact that on the Internet, especially on social media, most of the content is co-created.

It is my hope the legal situation surrounding digital legacies will improve in the next 10-20 years, so that everybody can claim their digital memories from these companies properly and legally. This will be especially important when the Internet's first and second generation get older.